Three years have passed since the EU regulation SFDR came into force, and the world has changed significantly since then. What is the current state of VC funds under Articles 8 and 9, and how will the market evolve in the coming years?

Three years have passed since the EU regulation SFDR came into force, and the world has changed significantly since then. What is the current state of VC funds under Articles 8 and 9, and how will the market evolve in the coming years?

SFDR – four letters intended to put an end to the greenwashing of financial products. Three years ago, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation came into force; this EU regulation aims to increase transparency regarding the sustainability of financial products. It requires financial market participants and advisors to disclose how their products consider environmental and social factors. The goal of the SFDR is to provide investors with clear information to facilitate sustainable investment decisions, distinguishing between products with explicit sustainable objectives and those without.

Work on the SFDR began in 2018 as part of the EU Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth. The process included public consultations and the development of technical standards before the regulation eventually came into effect in March 2021.

The SFDR is part of the broader Sustainable Finance context and is closely linked to the European Green Deal, the EU Taxonomy, and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). For more detailed explanations and impacts, see my blog posts: “Connecting the Pieces – Sustainable Finance” and “Impact of the EU Taxonomy on the European financial world.“

The SFDR brings significant changes to the financial industry:

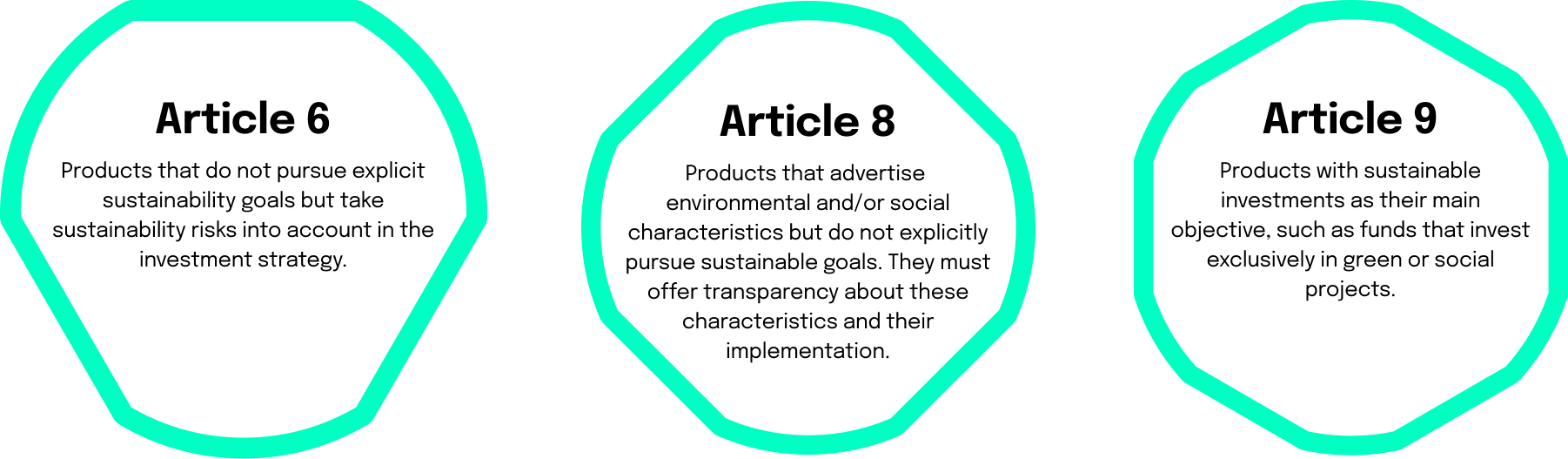

The SFDR classifies financial products into three categories, and its application is mandatory for all funds in the EU. Financial market participants and advisors must disclose whether and how they consider environmental and social criteria in their products. This includes products without sustainability objectives (Article 6), as well as those that explicitly promote environmental or social characteristics (Article 8) or pursue sustainable investments (Article 9).

The classification of a fund under the SFDR is not conducted by an external party but rather by the fund provider itself. The provider must transparently disclose the category of the fund and provide the relevant information. This self-classification is based on the fund’s sustainability characteristics and is subsequently reviewed by regulatory authorities to ensure compliance with SFDR requirements and prevent greenwashing.

Investors can find this information in pre-contractual documents, prospectuses, and on the providers’ websites. The disclosure requirements are uniformly regulated by the SFDR, ensuring that investors receive clear information to identify a fund’s sustainability category (Article 6, 8, or 9).

At neosfer, we are an active early-stage investor. The capital we invest in startups, however, does not come from Limited Partners (LPs) like traditional VC funds, but rather from our parent company, Commerzbank. As a result, we operate as a Corporate Venture Capitalist (CVC). Even though our refinancing strategy differs from that of a typical VC fund, we often find ourselves in a “co-opetition” relationship with other VC funds when selecting and closing investment opportunities – sometimes competing, but also cooperating at times. Given that VC funds are also subject to SFDR, this is a compelling reason for us to dive deeper into this topic.

VC funds are investment vehicles that raise capital from external investors, known as Limited Partners (LPs), to invest in promising startups. These startups often have the potential for high returns but come with increased risk. The fund managers, also known as General Partners (GPs), manage the capital and make investment decisions. The goal of a VC fund is to achieve high returns through the sale of company shares (Exit).

The main differences between VC funds and CVCs lie, apart from their refinancing strategy, primarily in their strategic orientation and investment horizon. CVCs are strategic investors; beyond financial returns, they aim to explore new technologies, business models, or markets to strengthen the core business of their parent company. CVCs can also have a longer investment horizon, as they often do not face the same exit pressure as traditional VC funds.

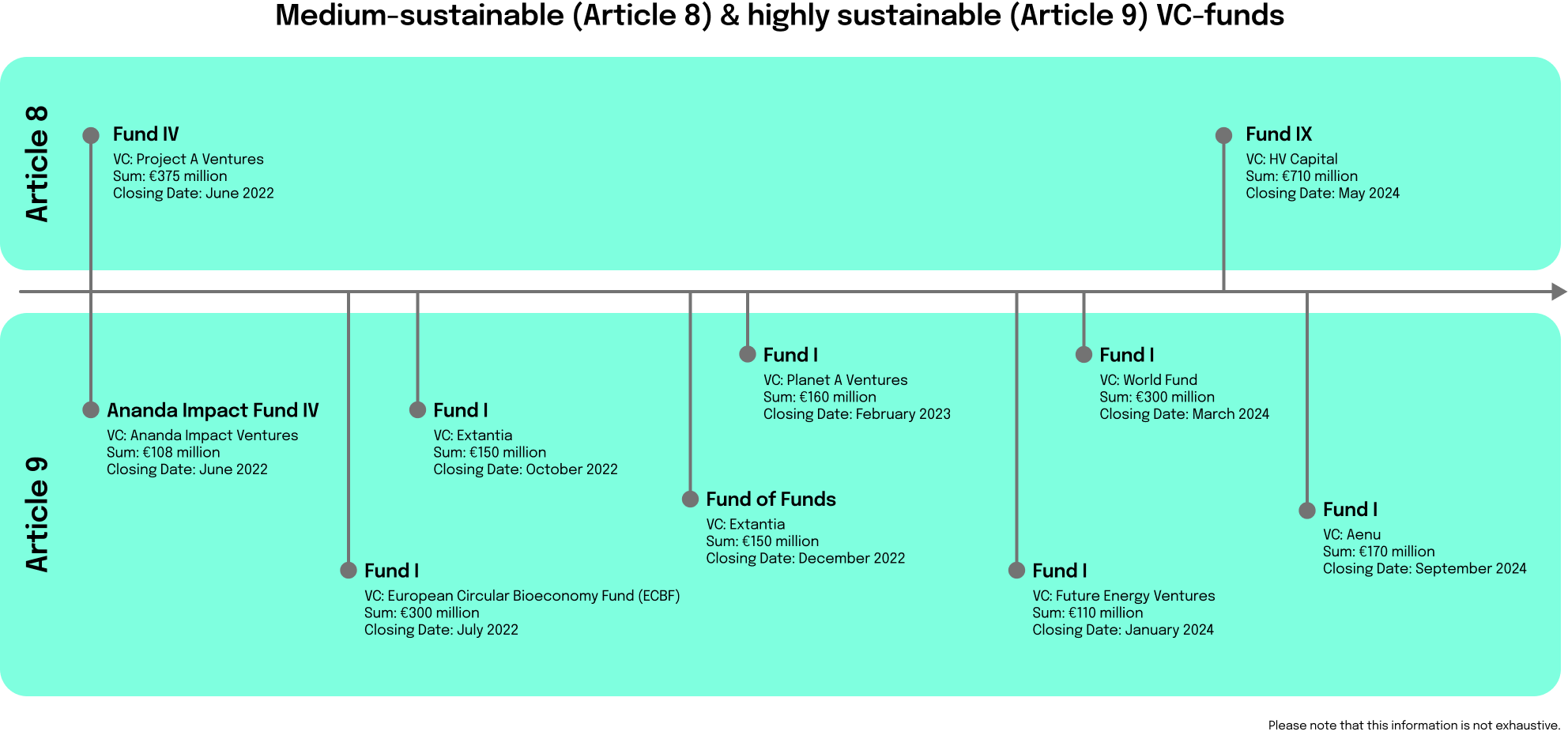

VC funds can be categorized under SFDR into three groups: Article 6, 8, and 9, depending on how strongly sustainability is integrated into their investment focus. Specifically, we have categorized funds as medium-sustainable (Article 8) and highly sustainable (Article 9) based on their sustainability focus.

Looking at this timeline, it becomes clear that the majority of German VC funds classified under Articles 8 and 9 follow the strict criteria of Article 9 of the SFDR—true to the motto “go big or go home.”

When considering the SFDR and its implementation today, it is important to acknowledge that the geopolitical and macroeconomic conditions have changed significantly since the regulation’s conception – affecting current investment strategies.

The Russian-Ukrainian war has ushered Europe into a new era of uncertainty. In addition to open conflicts, there are asymmetric and covert confrontations such as cyber warfare, proxy wars, and the global struggle for resources. The Ukraine is no longer available as a transit country for inexpensive gas from Russia. Geopolitically, Germany has cut its dependency on Russian energy. Combined with economic sanctions against Russia, this has led to higher energy prices, causing inflation and an economic downturn in Germany. While Germany has become more independent of Russian energy, the cost has risen significantly.

Macroeconomically, Germany is in a phase of stagnation, with growth rates hovering around zero. This has resulted in capital becoming scarcer and more expensive. VC funds – including those classified under Articles 8 and 9 of the SFDR – are finding it increasingly difficult to raise capital, and the associated costs have risen.

Sustainably produced energy is both a geopolitical solution and crucial for achieving climate goals. However, the transformation to renewable energy in Germany has yet to be completed. Due to macroeconomic changes, less capital is available for this transformation, despite its growing political importance.

Adding to these challenges is the high demand for DefenseTech, which also requires significant resources. This creates competition with Article 8 and 9 funds and their portfolio startups, as both talent and capital are in high demand.

Despite the geopolitical and macroeconomic challenges, there are signs of stabilization. Energy prices have recovered, and inflation has eased, prompting central banks to start lowering interest rates. Capital is becoming cheaper and more available. This generally offers hope for the next generation of Article 8 and 9 VC funds, as well as for sustainable startups that rely on this financing.

However, despite the easing of some pressures, the challenges remain – particularly the competition from DefenseTech. The next generation of funds is likely to be smaller – both in terms of the number of funds and the volume of available capital.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Brevo. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information